Contributed by Eugenia Hobday

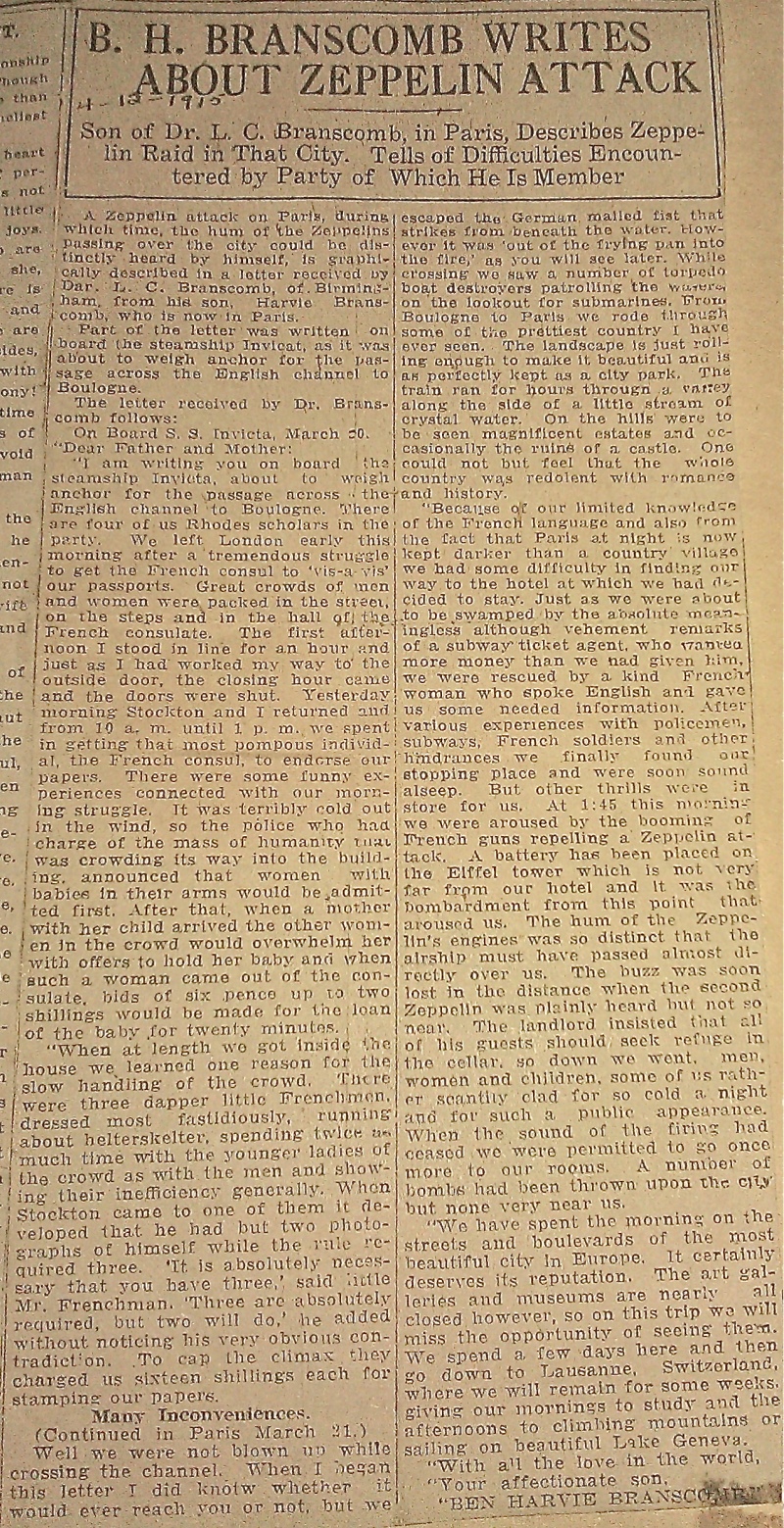

Harvie Branscomb describes zeppelin attack while in Paris

April 12, 1915

Dallas Morning News

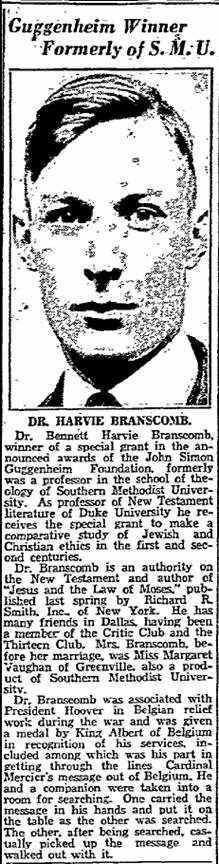

March 30, 1931

Dallas Morning News

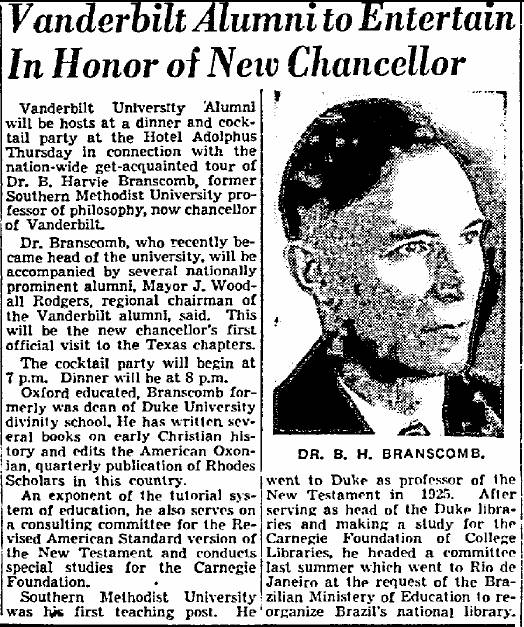

November 14, 1946

Vanderbilt's Debt to Alabama

The Anniston Star, August 15, 1946

Vanderbilt Chancellor Emeritus

Harvie Branscomb dies at 103

NASHVILLE, Tenn. - Harvie Branscomb, a theologian and educator who, as

Chancellor of Vanderbilt University from 1946 to 1963, put the institution on

the path to recognition as a national university, died July 24 at his home in

Nashville, Tennessee. Born in Huntsville, Alabama in 1894, he was 103 years

old.

Branscomb was a major figure on the national and international educational

scene. In 1947, President Harry S. Truman appointed him as the first chairman of

the U.S. Advisory Commission for Education Exchange, which he led for four

years. He later was named chairman of the Commission on Education and

International Affairs of the American Council of Education (1955-58). Branscomb

served as an educational consultant to the World Bank (1962-63), and he chaired

the U.S. Commission for UNESCO (1963-65).

Branscomb remained active in the years after he retired from Vanderbilt. He

was a member and vice-chairman of the U.S. Delegation to the Unesco General

Conference in Paris in 1964. The following year he chaired the U.S. Delegation

to the World Conference on the Eradication of Illiteracy held in Tehran. He

traveled to Geneva as a member of the U.S. Delegation to the World Health

Organization Assembly (1965 and 1966) and to Buenos Aires as chairman of the

U.S. Delegation to the Conference of Ministers of Education and Ministers in

Charge of Planning (1966).

"Faye and I are deeply saddened by the death of Harvie Branscomb," said

Vanderbilt Chancellor Joe B. Wyatt. "He has been a source of great wisdom and

counsel for me personally over the past 16 years and an integral part of

Vanderbilt University for more than half a century.

"So much of Vanderbilt's success today is a direct result of Harvie's

leadership. His influence is apparent in the University's facilities, its

governance, the quality of its students and faculty, and in its research

endeavors. Chancellor Branscomb realized early on the potential for Vanderbilt

to contribute to the nation's education and research efforts and first directed

the University toward becoming an institution of national stature, while

upholding the University's tradition of civility and integrity."

Educated at Birmingham College (later named Birmingham Southern), Harvie

Branscomb was the son of Lewis Capers Branscomb, a prominent Methodist minister.

In 1914, he won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, where he took First Honors in

Theology and won a coveted Greek Prize. Branscomb began his career as a New

Testament scholar, which required mastery of Greek, Hebrew and Latin. His

primary contribution was the study of the cultural and religious roots of

Christianity. He later authored four books on theology: "The Message of Jesus"

(1925), "Jesus and the Law of Moses" (1930), "The Teachings of Jesus" (1931) and

"The Gospel of Mark" (1937).

While Rhodes Scholars at Oxford, Branscomb and a fellow student, O.C.

Carmichael, were among a group of American student volunteers who worked for

Herbert Hoover's Commission for Relief in Belgium. The two smuggled a

politically sensitive letter from Cardinal Mercier through the German lines,

despite having the letter in their possession and being searched by German

troops. This letter to Belgian priests encouraged resistance to the German

invasion and was published in the London Times. For this they were awarded the

Medaille du Roi Albert, Medaille de la Reine (Belgium). Carmichael was later

Branscomb's predecessor as Chancellor of Vanderbilt.

After his return from Oxford, Branscomb served as a Lieutenant in the field

artillery, but the war ended before he saw action. He then moved to Southern

Methodist University in Dallas, where met Margaret Vaughan, daughter of a judge

in Greenville, Texas, who became his wife and partner for 71 years. While at

SMU, Branscomb championed the right to academic freedom of another junior

faculty member. In 1923 Branscomb took a year's leave of absence to complete

coursework for a Ph.D. in philosophy from Columbia University.

In 1925, Branscomb moved to Duke University, where he ultimately became dean

of the Divinity School. While at Duke, he served briefly as Director of

Libraries, and in 1940, under sponsorship of the Carnegie Corporation, he

published "Teaching With Books," demonstrating that libraries were seen

primarily as repositories for research materials, and were little used in class

room teaching. He also was decorated by the Brazilian government with the Order

of the Southern Cross for his work in reorganizing the National Library of

Brazil, while serving as chairman of the American Library Association Mission to

Brazil in 1945. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1931-32.

He also held honorary degrees from Brandeis University, Northwestern

University, Southern Methodist University, Columbia University, Southwestern

University, Birmingham-Southern and Hebrew Union College.

In 1946 Branscomb was appointed Vanderbilt's chief executive, only the fourth

chancellor since the University's founding in 1873. Under his imaginative and

forceful leadership, the University experienced dynamic growth in nearly every

area and began the transition from an excellent regional institution to one of

national prominence.

Branscomb is credited with transforming the selection process for nominees to

the Board of Trust in order to attract leaders of national as well as local

institutions. He recruited Harold Vanderbilt, great-grandson of founder

Cornelius Vanderbilt, to membership on the Board of Trustees. In an effort to

recruit and retain distinguished scholars and scientists to the University's

faculty, Branscomb urged the Board to reinforce the University's commitment to

academic freedom, raise faculty salaries and recruit distinguished faculty.

During his term as Chancellor, full-time student enrollment reached a

then-record level, even as test scores and grades continued to rise. The

University became a more diverse institution as students from around the country

were drawn to Vanderbilt, and in 1952 the University opened its doors to

minority students before the other private universities in the South did so.

By the time of Branscomb's retirement, the number of full-time faculty had

doubled, faculty salaries had almost tripled (in current dollars) and the number

of buildings on campus had more than doubled. The University's annual budget

increased by more than 400 percent, and the endowment increased from $38 million

in 1946 to $88 million in 1963 (market value). He rebuilt the Medical School,

which had been recommended for closure but became one of the outstanding

institutions in the nation.

Between 1953 and 1962, the schools of Engineering, Divinity and Law all

acquired their own buildings and 15 new residence halls were built, more than

doubling the number of buildings that existed on the campus prior to his tenure.

In 1963, Branscomb's final year as Chancellor, "Vanderbilt for the first time

ranked in the top 20 private universities in the United States," according to

the book "Gone With the Ivy," a biography of the University written by

Distinguished Professor of History Paul Conkin.

Branscomb maintained an active interest in University affairs in the years

after his retirement. Honored with the title Chancellor Emeritus, he maintained

an office in Kirkland Hall and regularly attended University functions. He

particularly enjoyed the celebration of his 100th birthday in December of 1994

at the residence of Chancellor and Mrs. Wyatt.

Chancellor Emeritus Alexander Heard, who succeeded Branscomb as chancellor,

said, "Chancellor Branscomb was both a hard man to follow and an easy man to

follow. His enormous achievements set a standard dauntingly high for a

successor, yet he and Mrs. Branscomb were incomparably hospitable to Jean and me

from our first day at Vanderbilt, and our friendship and gratitude remained ever

after. Chancellor Branscomb brought Vanderbilt to new levels of recognition,

quality and possibility."

Branscomb is survived by three sons, Harvie Branscomb Jr., attorney in Corpus

Christi, Texas; Dr. Ben Branscomb, distinguished professor emeritus of medicine

at the University of Alabama Medical School in Birmingham, Ala.; and Lewis M.

Branscomb, emeritus professor of public policy and corporate management at

Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. and member of the Vanderbilt Board of

Trust. He is also survived by his brother Lewis C. Branscomb, emeritus professor

at Ohio State University; two sisters, Dr. Louise Branscomb and Mrs. Charles L.

Dill, both of Birmingham, Ala.; nine grandchildren and nine

great-grandchildren.

A memorial service will be held Monday, July 27 at Vanderbilt University's

Benton Chapel at 4 p.m. Visitation will be held at Tillett Lounge in the

Divinity School from 2:30 to 4:00 p.m. In lieu of flowers, the Branscomb family

has asked that memorial donations be made to Vanderbilt University.

Branscomb Collection at Vanderbuilt University

Contributed by Penny Leggett

This collection of pre-Columbian Nasca pottery was assembled by Chancellor and Mrs. Harvie Branscomb. It is displayed in

Garland Hall in recognition of his deep interest in Latin American culture and scholarship and Vanderbilt University's

commitment to excellence in this field of study. The exhibit is made possible by a loan from his three sons, Harvie

Branscomb Jr., Ben V. Branscomb, and Lewis M. Branscomb.

Nasca culture thrived on the south coast of present-day Peru for several hundred years, from 200 BC to AD 600. This is a

harsh desert region where rivers often run dry, and life requires intimate knowledge of underground water sources and of

hardy plants and animals native to the region. The Nasca developed complex strategies, pragmatic and religious, to

understand and thrive in the world around them. We can only glimpse the content and meaning of Nasca myth and ritual in

archaeological ruins and on artistic media such as decorated pottery.

Intimate ties and concerns with the environment are reflected in highly developed artistic expressions. Perhaps best known

for creating breathtaking lines and geoglyphs, the Nasca also developed some of the most elaborate ceramic techniques in the

pre-Columbian Americas. Their slip-painted vessels displayed up to thirteen colors, and were fired in such a manner that

designs would be permanent. Iconographic style changed over time, beginning with relatively naturalistic images during the

Early Nasca, and ending with abstract, often highly complex images in Late Nasca.

Vessels include jars with bridged spouts, which served as bottles, and a variety of bowls and cups for ceremonial drinking

and feasting. Nasca pottery depicts images ranging from mythical themes such as the Killer Whale, to human figures like the

standing warrior, to naturalistic images that include hummingbirds, mice, spiders, and cactus. Vessels depict figures

inhabiting the natural, supernatural, and social worlds, all of which were ultimately inter-related in Nasca culture. Unlike

many pre-Columbian societies, elegant vessels like those in this collection were not restricted to high-status priests or

leaders. Rather they were available to nearly everyone.

Harvie Branscomb to be in Atlanta Army YMCA

Contributed by Penny Leggett

Contributed by Eugenia Hobday

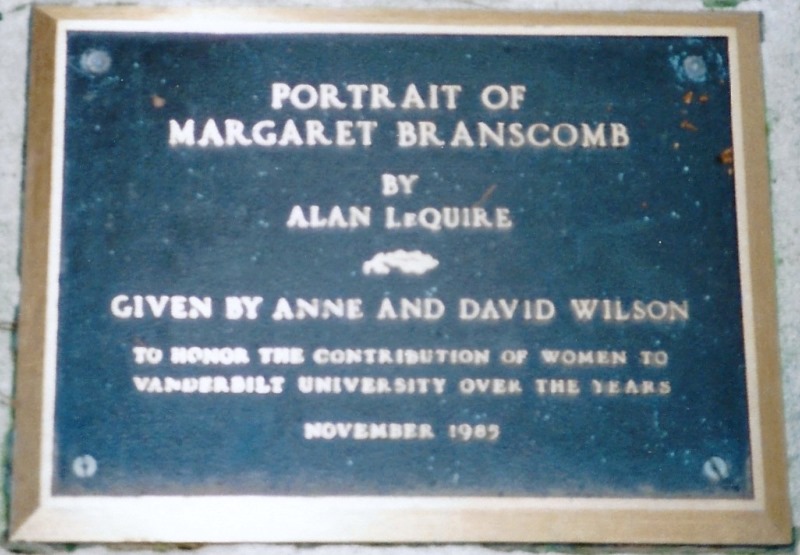

"Margaret Branscomb"

by Alan LeQuire

This bronze statue by Nashville sculptor Alan LeQuire honors Margaret Vaughan Branscomb,

wife of Harvie Branscomb, Chancellor of Vanderbilt from 1946 to 1963. Mrs. Branscomb was responsible for the planting of the Southern

Magnolias that now line the West End Avenue and Twenty-first Avenue South edges of campus. This artwork was unveiled in 1985.

The Vanderbilt garden club - Jean and Alexander Heard Library ...

VANDERBILT GARDEN CLUB RECORDS MSS # 473

Historical Note - A brief history of the Vanderbilt Garden

Many of the magnolia trees that encircle the campus were grown from seed propagated and planted under the direction of Jack

Lynn who worked for 27 years for the Building and Grounds Department. It was Margaret Branscomb (1896-1992), a long time

VGC member and wife of Chancellor Harvie Branscomb, who put forward this idea of the circle of magnolias during her time as

President of the VGC in 1954. Other trees were grown in nurseries and were gifts from individuals. These magnolias, which

were planted in the late 1950's, have reached maturity and stand as one of the most significant accomplishments of the

Vanderbilt Garden Club and certainly as Margaret Branscomb's and Jack Lynn's enduring gift to Vanderbilt University.

Contributed by Penny Leggett