History of

Stafford County, Virginia

Founded in 1664, created from Westmorland County and named for the English County of Stafford, Stafford County, Virginia, has

strong connections to events that shaped our nation's history. It was at Marlboro Point, that Indian Princess Pocahontas was

kidnapped and taken to Jamestown. Another historical figure also made Stafford his home. Augustine Washington, with the rest of

his family, including a six-year-old son named George, moved to Ferry Farm in 1738. The future firstpresident spent his formative

years there until he reached young adulthood.

Native Americans roamed and settled in the area known as Virginia centuries before the first documented Indian settlement in Stafford

County. Indians lived here as early as 1,000 B.C., hundreds of years before Pocahontas and English Captain John Smith visited these

shores. In 1647, the Brent family migrated from Maryland to establish the first permanent English settlement. Stafford County was

formed a few years later in 1664.

By the early 1700s, the Indians having dispersed, the county experienced a growth of farms, small plantations, gristmills and sawmills.

Mining and quarrying became important industries. Iron works furnished arms for the American Revolution. Aquia sandstone, quarried in

abundance, provided stone for the White House, the U.S. Capitol, and trim for private homes. After the destruction of Federal Buildings

in Washington, D.C., by the British during the War of 1812, quarries were reopened for a short time to aid reconstruction.

Gold mining became a leading industry in the southwestern portion of Stafford County in the 1830s. With the coming of the Richmond,

Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad to Aquia Creek in 1842, the county became vulnerable to troop movements during the Civil War.

Although Stafford County suffered no major battles, over 100,000 troops occupied the area for several years, stripping the county of

its livelihood, farmland, and vegetation. Families endured the loss of churches and private homes as they were used as impromptu

hospitals. Valuable records were also lost.

Prosperity did not return until World War I when the U.S. Marine Corps came to Quantico. At that time, the county was primarily

agricultural, with the exception of fishing industries situated along the Potomac River. In World War II, the wide expansion of the

Marine Corps base created new employment opportunities. A C.C.C. camp was located in southern Stafford County during this time.

With the completion of Interstate 95 in the 1960s and the recent addition of commuter rail, Stafford County is one of Virginia's

fastest growing localities. While encouraging industry, the county is trying to maintain its wonderful rural atmosphere.

St. William of York Parish

(Thanks to Glenda Kopchinski, our unofficial parish historian):

Sir William Fitzherbert of York, England, son of an earl, was a controversial religious leader who was the archbishop of England

in the 12th century. His mother was the half-sister of the King of England, making him the King's nephew. He was canonized in 1227 by

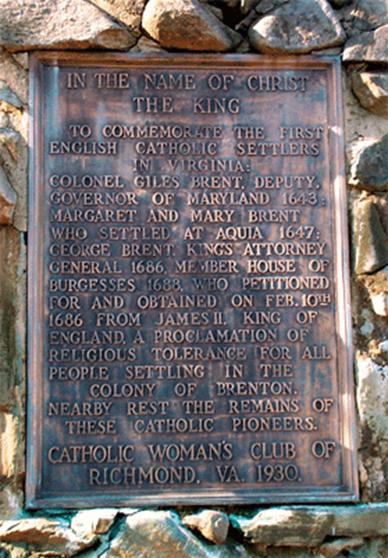

Pope Honorious III. Our parish community, which bears his name, traces its origin back to 1647, when the Brent family moved to Stafford

County to escape religious intolerance. Sir Giles Brent, an English Catholic nobleman who once served as Governor of Maryland, moved

from Baltimore to the Virginia wilderness near the mouth of Aquia Creek. In 1686, Captain George Brent was granted a patent of 30,000

acres of land lying between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers. The patent, granted by King James II, included a royal mandate assuring

them and later inhabitants of Virginia free exercise of their religion.

They established the town of Brenton, later called Aquia. In 1785, Bishop John Carol reported about 200 Catholics in this area. Little

more is known about the Catholic community here until almost 1900. The original cemetery of the lost community in Aquia was rediscovered

in 1897. In addition to the inhabitants of the pioneer settlement, a monument was discovered to Spanish Jesuit priests who were martyred

in 1687 while trying to convert the local Indians to Catholicism.

During the 1920's, Bishop O'Connell purchased the land containing the cemetery and gave the job of its restoration to the Richmond

Catholic Women's Club. A brick wall was built around the cemetery and an altar was erected. On October 6, 1929, the first field Mass was

celebrated in the cemetery. One year later the large crucifix, which still stands on Route 1 at the entry to the Widewater District of

Stafford County, was unveiled and dedicated. It, too, was erected by the Richmond Catholic Women's Club.

The Brent Family

Catholics were not officially granted the right to worship as they pleased in Virginia until after the General Assembly passed the

"Act for Establishing Religious Freedom" in 1785. They were present in the colony long before then, of course - starting with the Spanish

missionaries in 1570. The individual Catholic families were vulnerable to fines or censure until James Madison maneuvered the approval of

the legislation that Thomas Jefferson had first introduced in 1779.

That law was thus proposed when it appeared the American Revolution might fail. It was adopted three years before the Constitution

was ratified, and six years before the First Amendment ("Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech...") made the Federal protection of religious freedom explicit.

The Brent family initially chose to settle in Maryland, and Margaret Brent was so close to Governor Leonard Calvert (brother of Lord

Baltimore) that she served as the executor of his estate. (In the process, she asked for the right to vote, and is often mentioned as the

first suffragette and first female lawyer in America).

However, the political conflicts in Maryland were intense, including several small-scale civil wars, and the Brents moved to Virginia.

Margaret Brent was the first English owner of what today is Alexandria. She and her brother Giles were the first English settlers in

Northern Virginia.

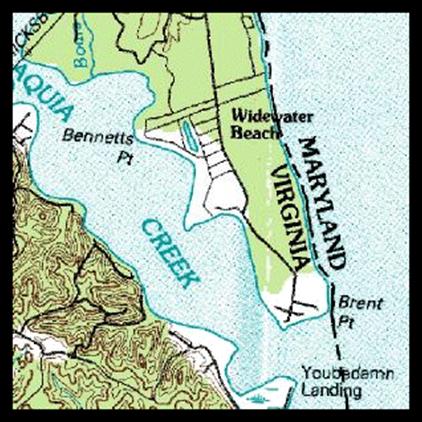

She built a plantation called "Retirement" while he built "Peace" near Brents Point on Aquia Creek, in what was Northumberland County but

is now Stafford County. Giles married Kittamaquad (also spelled as Chitamachen), the daughter of the Piscataway Tayac or chief - just as

John Rolfe married Pocahontas, the daughter of Chief Powhatan. Giles Brent's marriage provided him a potential claim to the lands of the

tribe, including those of his son Giles Jr.

Brent ended up needing the governor and the Governor's Council of Virginia to affirm that his claim to the land on Aquia Creek was based

on a grant from the Virginia colonial government. Lord Baltimore tried to claim that he was entitled to issue a grant to someone else for

the land where Brent had settled, because (according to Lord Baltimore...) Potomac Creek marked the Maryland-Virginia boundary.

Giles' nephew, George Brent, later built "Woodstock" on Aquia Creek. He was the only Catholic elected to the colonial Virginia House of

Burgesses. The Arlington Diocese of the Catholic Church owns the property of George Brent and has excavated at the site of his colonial

home, "Woodstock".

George Brent married the step-daughter of the third Lord Baltimore, maintaining the close ties with the Catholic proprietor across the

Potomac River. George Brent had a different relationship with the Native Americans than his uncle Giles, however. In 1675, George Brent

led a militia response to the presumed murder of a frontier herdsman by a Doeg Indian. That ended up including a raid across the Potomac

River and an attack on settlements in Maryland that resulted in the death of numerous innocent Susquehannock Indians:

Capt. Brent went to the Doegs' cabin (as it proved to be) who speaking the Indian tongue called to have a "matchacomicha, weewhio," i.e.

a councill called presently such being the usuall manner with Indians) the king came trembling forth, and wou'd have fled, when Capt. Brent,

catching hold of his twisted lock (which was all the hair he wore) told him he was come for the murderer of Robert Hen, the king pleaded

ignorance and slipt loos, whom Brent shot dead with his pistoll, th' Indians shot two or three guns out of the cabin, th' English shot into

it, th' Indians throng'd out at the door and fled, the English shot as many as they cou'd, so that they killed ten, as Capt. Brent told me,

and brought away the king's son of about 8 years old, concerning whom is an observable passage, at the end of this expedition; the noise

of this shooting awaken'd the Indians in the cabin, which Coll. Mason had encompassed, who likewise rush'd out and fled, of whom his

company (supposing from that noise of shooting Brent's party to be engaged) shott (as the Coll. informed me) fourteen before an Indian came,

who with both hands shook him (friendly) by one arm saying Susquehanoughs netoughs i.e. Susquehanough friends and fled, whereupon he ran

amongst his men, crying out "for the Lords sake shoot no more, these are our friends the Susquehanoughs".

In 1686, all was quiet on the northern front. George

Brent and three partners obtained a grant from the Crown - one of the last

before the Culpepper family took control of their claim to all the land between

the Rapahannock and Potomac Rivers<, ultimately known as the Fairfax Grant. They also

received a special dispensation from James II so settlers on their grant would have freedom

to worship in their own manner. Brent and his partners were planning to recruit Huguenots

(French Protestants) to the Brent Town tract, south of modern-day Brentsville in what are now

Prince William and Fauquier counties. (It was part of Stafford until 1731). Later, the real

estate speculators sought to recruit Catholics to move to their inland parcel, but were unsuccessful.

There's a large crucifix on Route 1 north of Fredericksburg, honoring

the Brent family role in establishing "religious liberty" in Virginia. Like so many other Virginia

traditions, the facts may not support the claims

completely. The Brents deserve acknowledgement as pioneers, and they clearly

were Catholic, but the Brent Town project was a real estate venture motivated

by a hope of profit and targeted initially towards Protestants, rather than a

pioneering initiative to establish religious freedom for Catholics in Virginia.

A History of

George Washington's River Farm

Courtesy of the American Horticultural Society

Copyright 1998-2004 American Horticultural Society. All rights reserved.

River Farm's first English family was the Brents, a Catholic

family who played an active role in the early colonial life of Maryland. Captain Giles

Brent originally landed in Jamestown, Virginia but in 1638 returned

from a trip to England accompanied by his sisters, Margaret and Mary, to settle

in St. Mary's County, Maryland. The family was related to Lord Baltimore, the

King's proprietor in Maryland, and their life in the colony was closely

associated with that of Lord Baltimore's brother, Leonard Calvert, the resident

governor.

Margaret Brent has been described as the first American

feminist - a women who was a lawyer and landowner who petitioned the Maryland legislature

for the vote. Through the family relationship, but also due to her own

unique abilities, she became executrix for Leonard Calvert upon his death. Lord

Baltimore, weeks distant in England, misinterpreted Margaret's action in

settling Calvert's debts and wrote an acrimonious letter requesting that the

Brents leave Maryland. The Maryland legislature, which had had its own problems

with this assertive woman, arose as a man to her defense and in a letter signed

by the entire body told Lord Baltimore that he could not be better represented

by any man in the colony. In fact, Margaret was referred to in Maryland records as Margaret Brent, Gentleman.

However, in 1647 - even before Lord Baltimore's letter

reached them - the Brents, weary of the political battles with the Calverts and

disheartened by religious dissension between Protestants and Catholics in Maryland, had

already left the colony to settle near Aquia in Virginia. In 1100%/54, Giles

Brent received patents totaling 1,800 acres from Thomas, Lord Culpepper for his

year-old son, Giles, Jr. Giles' wife was a princess of the Piscataway tribe of

Native Americans who had been entrusted to Margaret Brent as a child by her

father, a convert to Christianity. She was raised in the Brent household and at

the age of 16 was married to Giles, 30 years her senior. The grant of 1,800

acres in their child's name was named Piscataway Neck and included the land which

is now River Farm.

Giles, Jr. was never at ease with the local Dogue tribe,

or, it seems, anyone else. It has been stated that his encounters with the

native tribe were a precursor to Bacon's Rebellion, and at home his treatment

of his wife was so violent that she obtained a legal separation in 1679, the

first in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Giles returned to England where he died in

September of that year. Piscataway Neck passed to a cousin, George

Brent, and through him to a brother-in-law, William Clifton, in 1739.

Upon inheriting title to the land, William Clifton

renamed the property Clifton's Neck. By 1757, Clifton built a brick house on

the property which, much enlarged and remodeled over the subsequent two

centuries, now serves as the headquarters of the American Horticultural

Society.

In 1745, the Virginia General Assembly in Williamsburg had

authorized a public ferry to run between Clifton's neck and Broad Creek

in Maryland to connect with the King's Highway to the north. This highway was

the main thoroughfare running from Georgia in the south up the east coast

through Annapolis to Philadelphia and New York. As a result, Clifton's Ferry

was a busy establishment, and George Washington made many references to it in

his diaries.

Clifton operated an inn at the ferry landing where,

according to the later historian William Snowden, "the traveler always found

under its roof an abundance of good fare; for the river was so stocked with the

fresh fish and the forests around abounded with wild game; and there was no

stint for apple brandy, cider and beer, old jamaica and other beverages for all

who were inclined in that direction and most folks were so disposed in those

primitive times". Adjacent to the inn was a dueling ground which was used

frequently, if illegally, by local residents

Despite his inn's prime location, Clifton suffered

business losses and as early as 1755 advertised part of his holdings for sale.

Gentleman farmer George Washington of neighboring Mount Vernon was desirous of

buying this land but because of what he described in his diaries as Clifton's

"shuffling behavior" it was not until 1760 that Washington obtained clear title

to the 1,800 acres for payment of £1,210 at the equivalent of a bankruptcy

sale. To be fair to Clifton, not all the "shuffling" was his fault. At Mrs.

Clifton's insistence only a portion of the property was first offered, the

house and surrounding land to be retained for the Cliftons' use. Washington refused

to buy the reduced package. It was not until Clifton was forced to

submit to a commissioner's sale - Washington was a member of the commission -

that Washington acquired the entire property and changed its name to River

Farm.

Thus River Farm became the northernmost of Washington's five

farms, and today's River Farm is located on the northernmost division of

that property. Although Washington had patiently pursued the acquisition of the

property, he never actually lived on or worked this land. Instead, he preferred

to rent it, first in 1761 to tenant farmer Samuel Johnson who paid ever

increasing amounts of his tobacco crop to Washington for the privilege. The

farm was even once offered for sale in 1773, but instead Washington held on to

it and later gave its lease as a wedding present to one Tobias Lear whose

bride, Fanny Bassett, was Martha Washington's niece and widow of George

Washington's nephew, George Augustine Washington.

Tobias had come to Virginia in 1786 on the

recommendation of a mutual friend to be secretary to Washington and tutor to

Martha's two grandchildren. He was treated as a member of the family, taking

his meals with them. He served Washington not only as secretary but as a

personal confidante at Mount Vernon as well as in Philadelphia and New York while

Washington served as the young nation's first President. He was at Washington's side

when he died. In his will, Washington gave Lear use of the farm, rent

free, for his lifetime. Tobias' wife Fanny predeceased him, and he installed

his mother-in-law and children at the farm while he preferred to reside in Georgetown. It

is said he died there, a suicide, in 1816. However, evidence of his

spiritual presence at River Farm continues to this day.

Tobias Lear had called the property Walnut Farm. Today,

in the meadow below the "ha-ha" wall, three venerable old black walnut trees

still stand, reminders of the 18th century landscape that Lear and Washington

knew. Another of River Farm's trees with strong associations with Washington is the

Kentucky coffee tree, so named for its native origin and its seeds use as

a coffee substitute. Washington introduced the species to Virginia when he

returned to Virginia from one of his surveying trips in the Ohio River valley

and successfully germinated seeds he had collected there. There are several

specimens of the Kentucky coffee tree at River Farm, descendants of those first

trees grown by Washington.

The oldest tree standing on River Farm toady is the

immense Osage range, a tree native to the western United States. This specimen,

the largest in Virginia and second largest in the country, is located in the

shade garden to the north of the main house. It is believed to have been a gift

from Thomas Jefferson to the Washington family. It is known that Jefferson received

seedlings of the Osage orange from the Lewis and Clark expedition of

1804-06.

After Tobias Lear's death, the farm was occupied by two

generations of the Washington family: George Fayette Washington, a nephew, and

Charles Augustine Washington, a great-nephew. In 1859, a century after Washington

purchased the property from Clifton, Charles Augustus sold 652 acres of River

Farm to three Quaker brothers, Stacey, Isaac, and William Snowden of New Jersey. The

Snowdens and other Quaker families came to the Woodlawn-Mount Vernon area in

1845 for two reason: the availability of hardwood timber to be used in New England

shipyards, and the eschewance of slave labor in the area. The Snowdens divided

the acreage, then known as Wellington, into three sections. Isaac Snowden and

his wife lived in the house that still stands at River Farm.

In 1866, 280 acres including the present-day River Farm

were sold to three men known as "The Syndicate." A writer from The Washington

Sunday Star visited the estate in 1904 and referred to it as "this broken and

pathetic house." The Wellington property was subsequently purchased in 1912 by

Miss Theresa Thompson, a member of a prominent local family that owned and

operated Thompson's Dairy, a business concern active in the area until the

1960s. Miss Thompson made changes and improvements at Wellington, but it was

Malcolm Matheson, who bought the property in 1919, to transform it into the

charming early-20th century country estate we know today. The evocative 18th

century-style paneling in the ground floor rooms, the welcoming foyer, and the

light-filled ballroom were all part of Mr. Matheson's reconstruction of the

house. Out-of-doors he cleared acres of honeysuckle, briar, and blackberry to

plant boxwood, magnolia, wisteria, and other ornamentals to create a serene

park-like setting for his family.

Wellington faced one more upheaval. In 1971, Mr.

Matheson decided to sell his home, and the Soviet Embassy offered to buy the

property for use as a retreat or dacha for its staff. In the lingering Cold

War, many people, locally and across the country, objected to the thought of

George Washington's farm becoming the possession of the Soviet Union. As a

result, Congress and the Department of State asked Mr. Matheson to withdraw the

property from the market.

Among those concerned by the potential sale was Enid

Annenberg Haupt, philanthropist, gardener, and member of the Board of Directors

of the American Horticultural Society. Through her exceeding generosity, the

Society was able to purchase the 27 acres then comprising the Wellington

estate, agreeing to keep the property open for the enjoyment of the American

people. In honor of George Washington, one of our nation's first great

gardeners and horticulturists, the property was again named River Farm. In

1973, AHS moved its headquarters form the city of Alexandria to River Farm.

First Lady Patricia Nixon joined Mrs. Haupt at the dedication of the property

and together planted a ceremonial dogwood tree in the garden.

With the donation of a comprehensive master plan by AHS

Board member Geoffrey L. Rausch of Environmental Planning & Design in Pittsburgh, AHS

will make River Farm a living example of the Society's principles. The

master plan will be implemented over time as funding is secured for each

segment. Funds will be raised not only for the installation of the master plan

sections but also for their long-term maintenance. Our goal is to build an

endowment that will ensure the preservation of River Farm and its contributions

to American life for generations to come.

River Farm serves as the headquarters of the American Horticultural Society (AHS)

For further information about the current occupants

of River Farm, the American Horticultural Society, visit History of River Farms